Birth Trauma and Maternal Mental Health Fact Sheet

We are committed to curating the latest information in perinatal mental health to help educate healthcare providers, birth workers, and policymakers. This fact sheet is the screen reader version for those who prefer to consume their information in this format. We also have a PDF version available with the same information.

Download the Birth Trauma and Maternal Mental Health Fact Sheet.

Key Facts: Maternal Mental Health (MMH) Conditions

1 in 5 Mothers Are Impacted by Mental Health Conditions

Maternal mental health (MMH) conditions are the MOST COMMON complication of pregnancy and birth, affecting 800,000 families each year in the U.S. [1,2]

Mental Health Conditions Are the Leading Cause of Maternal Deaths

Suicide and overdose are the LEADING CAUSE of death for women in the first year following pregnancy. [3]

Most Women Are Untreated, Increasing Risk of Negative Impacts

75% of women impacted by maternal mental health conditions REMAIN UNTREATED, increasing the risk of long-term negative impacts on mothers, babies, and families. [4]

$14 Billion: The Cost of Untreated Maternal Mental Health Conditions

The cost of not treating MMH conditions is $32,000 per mother-infant pair, or $14 BILLION each year in the U.S. [5]

Certain Individuals are at Increased Risk for Experiencing MMH Conditions

High-risk groups include people of color, those impacted by poverty, military service members, and military spouses. [6,7]

It's Not Just Postpartum Depression: There are a Range of MMH Conditions

MMH conditions can occur during pregnancy and up to one year following pregnancy and include depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar illness, psychosis, and substance use disorders. [8]

Learn More about Maternal Mental Health Conditions

Learn more about maternal mental health conditions with our Maternal Mental Health Fact Sheet.

Key Facts: Birth Trauma and Maternal Mental Health

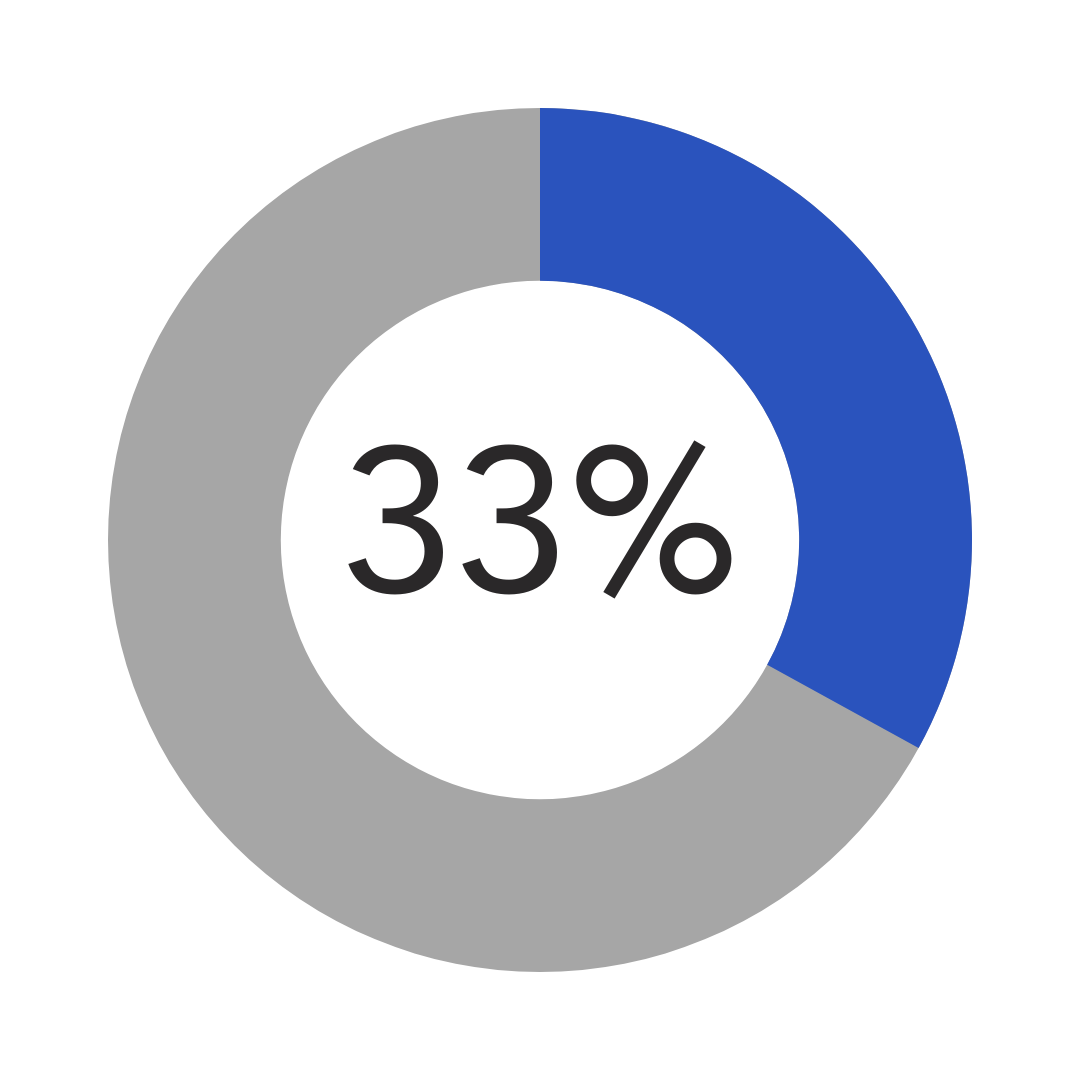

1 in 3 birthing people report feeling traumatized by their childbirth experience. [11]

1 in 5 birthing people report experiencing some form of mistreatment during

pregnancy or childbirth. [12]

What is birth trauma?

Birth trauma, or a traumatic childbirth experience, refers to the birthing person’s experiences of interactions and/or events directly related to childbirth that cause overwhelming and distressing emotions, leading to short- and/or long-term negative impacts on the birthing person’s health, wellbeing, and relationships. [9]

A leading factor contributing to birth trauma is the birthing person's perception or experience of poor interpersonal care and/or communication. [13]

Women of color are at increased risk for both poor interpersonal care and obstetric complications, increasing their risk for experiencing birth trauma. [14]

The same birth can be experienced very differently by the patient, partner / witness, and provider. [15]

Birth trauma can lead to a range of MMH conditions, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). [36]

Trauma is in the eye of the beholder.

It depends on the subjective experience of the event. Two people may be present at the same event but may have very different experiences.

“What a mother perceives as birth trauma may be seen quite differently through the eyes of obstetric care providers, who may view It as a routine delivery and just another day at the hospital.” [10]

— Cheryl Tatano Beck

Quotes from Women who have Experienced Birth Trauma

[25, 26]

“The labor care has hurt deep In my soul and I have no words to describe the hurt.”

“I was treated like nothing.”

“I felt coerced into decisions or was mocked or rushed. It was a very dehumanizing and frustrating experience.”

“I hated being shouted at by the midwife. She was abusive and downright mean.”

“I was offered WIC repeatedly though I explained that I did not qualify. I believe it was because I am Latina and my partner is Black that we were repeatedly offered WIC.”

“When I mentioned my desires, I was belittled and made to feel incompetent.”

“I strongly believe my PTSD was caused by feelings of powerlessness and loss of control of what people did to my body.”

“I felt raped and my dignity was taken from me.”

“I am amazed that 3.5 hours in the labor and delivery room could cause such utter destruction in my life. It truly was like being the victim of a violent crime or rape.”

Factors Contributing to Birth Trauma

Physical Factors [16, 17]

Definition: Significant physical injury, or threat / fear of injury or death, to the birthing person or to the baby. This includes obstetric interventions and maternal, infant, or postpartum complications.

Examples:

Emergency C-section or instrumental vaginal delivery

Experience of overwhelming pain or the denial of pain relief

3rd or 4th degree perineal lacerations or tears

Unwanted or unannounced episiotomy

Complications with anesthesia

Manual removal of placenta

Urinary catheterization

Unplanned hysterectomy

Hemorrhage

Preeclampsia

Stillbirth/ infant death

Premature birth

Fetal distress or harm to baby

Separation from infant in NICU

Psychological Factors [18, 19]

Definition: Threats generated by reproducing earlier psychological states (prolonged fear, terror, etc.), related to previous personal experience and/or intergenerational trauma.

Examples:

A birthing person who experienced sexual trauma earlier in life relives the trauma during childbirth.

A woman who was hospitalized for severe sciatica 20 years earlier relives the experience when the epidural needle she receives during labor hits a nerve.

A Black woman who is incarcerated is shackled during labor, raising the specter of the violence of slavery.

Care-Related Interpersonal Trauma [20, 21, 22, 23]

Definition: Threats to psychological safety brought about by negative interactions with providers and/or the maternity care system itself.

Examples:

Feeling disrespected by health care providers.

Feeling abandoned or alone.

Feeling pushed, rushed, coerced, not seen or heard.

Feeling that embodied knowledge is disregarded.

Being yelled at, ignored, scolded, or threatened.

Poor communication (lack of proper translation, spotty and inadequate conveyance of important information, partial informed consent, un/misinformed by healthcare personnel, etc.)

Lack of agency; loss of control and participation in decision-making.

Medical providers talking about the birth as if the patient were not present.

Obstetric Violence and Mistreatment

Disrespect of Patient Rights

Obstetric violence occurs when a birthing person experiences mistreatment or disrespect of their rights, including being forced into procedures against their will, at the hands of medical personnel. [27]

Loss of Autonomy

Mistreatment can also include loss of autonomy, being shouted at, scolded, or threatened, or being ignored. [27]

Invasive, Painful Treatments

Patients can be subjected to painful gynecological procedures and invasive treatment without consent during pregnancy and childbirth. [27]

1 in 5 U.S. Moms Experience Mistreatment

20% of U.S. mothers report experiencing some form of mistreatment during pregnancy and delivery care. Mistreatment during maternity care was higher among Black (30%), Hispanic (29%), and multiracial (27%) women. [28]

Impacts of Racism on Birthing People

Complications, Deaths Higher for Women of Color

Women of color are 3-4 times more likely to experience complications during pregnancy and childbirth and die from these complications than white women. [31]

Intergenerational Trauma from Procedures Tested on Black Women without their Consent

Black women enter pregnancy and childbirth suffering the impacts of intergenerational trauma, including the knowledge that many obstetric and gynecologic procedures were tested on Black women without their consent and without pain medication. [29]

Institutional Racism Results in Lower Quality of Care

Institutional racism in health care settings contributes to Black women receiving lower quality of care, such as giving birth in lower-quality hospitals and being subject to dangerous, demeaning, or humiliating treatment. [30, 31]

Dismissal of Black Women in Treatment Decisions

Black women are often dismissed and not included as active participants in care decisions and treatment, increasing their risk of birth trauma. [22, 29]

Individuals who experience birth trauma often attribute it to…

Individuals who experience birth trauma often attribute the cause of their experience primarily to 1) lack and/or loss of control and 2) issues of communication and practical/emotional support.

They often believe that their trauma could have been reduced or prevented by better communication and support from their medial provider or if they themselves had asked for more or fewer interventions. [24]

Impacts of Birth Trauma

Maternal Mental Health Conditions

An estimated 4-6% of birthing people experience PTSD, and approximately 17% of birthing people will experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress. [37]

Significant Psychological Distress

Birth trauma can cause significant psychological distress or harm to the birthing person, affecting both physical and mental health, and frequently impacting future reproductive health and decision-making. [36]

Impact on Relationships

Birth trauma can negatively impact relationships between the parent and the infant (parent-child attachment in general and breastfeeding in particular); the partner (both emotional and sexual intimacy), and other children in the family. [32]

Impact on Others Present During Labor and Delivery

Others present at the birth, including the father / partner and medical providers, may also be impacted by birth trauma. [33]

"It is the birthing person's subjective experience of being traumatized that is the starting point for healing interventions."

— Leslie Butterfield, PhD

Birth Trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress

Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress [34]

Intrusive symptoms such as recurrent distressing memories, dreams, or flashbacks.

Intense, prolonged distress and/or physiological reactions such as sweating, nausea, or trembling upon exposure to an aspect of the trauma.

Alterations in arousal or reactivity, such as hyper-vigilance, irritability, inability to concentrate, or sleep disturbances.

Efforts to avoid people, places, thoughts, feelings, or conversations associated with the trauma.

Risk Factors for Pregnancy or Childbirth Related Post-Traumatic Stress [35]

Depression or anxiety during pregnancy.

Fear of childbirth (tokophobia).

Complications during pregnancy or childbirth.

Lack of support during childbirth.

Dissociation during childbirth.

History of sexual trauma.

Previous experience of fertility issues or pregnancy loss.

Recommended Reading

By Cheryl Tatano Beck, Jeanne Watson Driscoll, and Sue Watson

By Maria Muzik and Katherine Rosenblum

By Lynn Maden

By Nora Swan-Foster

Learn More About Birth Trauma

Don’t want to miss another fact sheet? Sign up for our newsletters!

Editorial Team

This fact sheet was prepared with input from Leslie Butterfield, PhD and Dr. Terri Wright, PhD, MPH. This fact sheet was funded by grants from the California Health Care Foundation and the W.K.Kellogg Foundation.

Citations

Fawcett, E. J., Fairbrother, N., Cox, M. L., White, I. R., & Fawcett, J. M. (2019). The Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: A Multivariate Bayesian Meta-Analysis. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 80(4), 18r12527. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18r12527.

Gavin, N. I., Gaynes, B. N., Lohr, K. N., Meltzer-Brody, S., Gartlehner, G., & Swinson, T. (2005). Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106(5 Pt 1), 1071–1083. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db.

Trost, S., Beauregard, J., Chandra, G., Njie, F., Berry, J., Harvey, A. & Goodman, D. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/data-mmrc.html.

Byatt, N., Levin, L. L., Ziedonis, D., Moore Simas, T. A., & Allison, J. (2015). Enhancing Participation in Depression Care in Outpatient Perinatal Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Obstetrics and gynecology, 126(5), 1048–1058. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001067.

Luca, D. L., Margiotta, C., Staatz, C., Garlow, E., Christensen, A., & Zivin, K. (2020). Financial Toll of Untreated Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders Among 2017 Births in the United States. American journal of public health, 110(6), 888–896. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305619.

United States Government Accountability Office, (2022). Defense Health Care: Prevalence of and Efforts to Screen and Treat Mental Health Conditions in Prenatal and Postpartum TRICARE Beneficiaries. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105136.pdf.

Taylor, J., Novoa, C., Hamm, K. & Phadke, S., “Eliminating Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Mortality: A Comprehensive Policy Blueprint,” Center for American Progress, May 2019. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/eliminating-racial-disparities-maternal-infant-mortality.

Postpartum Support International, (2023). https://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/.

Leinweber, J., Fontein-Kuipers, Y., Thomson, G., Karlsdottir, S. I., Nilsson, C., Ekström-Bergström, A., Olza, I., Hadjigeorgiou, E., & Stramrood, C. (2022). Developing a woman-centered, inclusive definition of traumatic childbirth experiences: A discussion paper. Birth (Berkeley, Calif.), 49 (4), 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12634.

Beck C. T. (2004). Birth trauma: in the eye of the beholder. Nursing research, 53(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200401000-00005.

Pidd, D., Newton, M., Wilson, I., & East, C. (2023). Optimising maternity care for a subsequent pregnancy after a psychologically traumatic birth: A scoping review. Women and birth. Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 36(5), e471–e480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2023.03.006.

Salter, C., Wint, K., Burke, J., Chang, J.C., Documet, P., Kaselitz, E., Mendez, D. (2023). Overlap Between Birth Trauma and Mistreatment: A Qualitative Analysis Exploring American Clinician Perspectives on Patient Birth Experiences. Reproductive Health, Apr21;20(1):63. https://doi: 10.1186/s12978-023-01604-0.

Reed, R., Sharman, R., & Inglis, C. (2017). Women's descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions. BMC pregnancy and childbirth,17(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1197-0.

Njoku, A., Evans, M., Nimo-Sefah, L., & Bailey, J. (2023). Listen to the Whispers Before They Become Screams: Addressing Black Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the United States. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 11(3), 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030438.

Bingham, J., Agwu Kala, F., Healy, M. (2023). The Impact on Midwives and Their Practice After Caring For Women Who Have Traumatic Childbirths: A Systematic Review. Birth. 2023;00:1–24. Published online August 21, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12759.

Handelzalts, J. E., Waldman Peyser, A., Krissi, H., Levy, S., Wiznitzer, A., & Peled, Y. (2017). Indications for Emergency Intervention, Mode of Delivery, and the Childbirth Experience. PloS one, 12(1), e0169132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169132.

Falk, M., Nelson, M., & Blomberg, M. (2019). The impact of obstetric interventions and complications on women's satisfaction with childbirth a population based cohort study including 16,000 women. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 19(1), 494. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2633-8.

Beck, C.T. (2004) Birth trauma: in the eye of the beholder. Nursing research53(1):p 28-35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200401000-00005.

Dufresne, L. (2023) Pregnant Prisoners in Shackles. Voices in Bioethics (9) https://doi.org/10.52214/vib.v9i.11638.

Hollander, M. H., van Hastenberg, E., van Dillen, J., van Pampus, M. G., de Miranda, E., & Stramrood, C. A. I. (2017). Preventing traumatic childbirth experiences: 2192 women's perceptions and views. Archives of women's mental health, 20(4), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0729-6.

Reed, R., Sharman, R., & Inglis, C. (2017). Women's descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 17(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1197-0.

Vedam, S., Stoll, K., Taiwo, T. K., Rubashkin, N., Cheyney, M., Strauss, N., McLemore, M., Cadena, M., Nethery, E., Rushton, E., Schummers, L., Declercq, E., & GVtM-US Steering Council (2019). The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2.

Watson, K., White, C., Hall, H., & Hewitt, A. (2021). Women's experiences of birth trauma: A scoping review. Women and birth: journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 34(5), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.016.

Hollander, M. H., van Hastenberg, E., van Dillen, J., van Pampus, M. G., de Miranda, E., & Stramrood, C. A. I. (2017). Preventing traumatic childbirth experiences: 2192 women's perceptions and views. Archives of women's mental health, 20(4), 515–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-017-0729-6.

Beck C. T. (2004). Birth trauma: in the eye of the beholder. Nursing research, 53(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-200401000-00005.

Vedam, S., Stoll, K., Taiwo, T. K., Rubashkin, N., Cheyney, M., Strauss, N., McLemore, M., Cadena, M., Nethery, E., Rushton, E., Schummers, L., Declercq, E., & GVtM-US Steering Council (2019). The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2.

Vedam, S., Stoll, K., Taiwo, T. K., Rubashkin, N., Cheyney, M., Strauss, N., McLemore, M., Cadena, M., Nethery, E., Rushton, E., Schummers, L., Declercq, E., & GVtM-US Steering Council (2019). The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023). One in Five Women Reported Mistreatment While Receiving Maternity Care. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/s0822-vs-maternity-mistreatment.html.

Chambers, B. D., Taylor, B., Nelson, T., Harrison, J., Bell, A., O'Leary, A., Arega, H. A., Hashemi, S., McKenzie-Sampson, S., Scott, K. A., Raine-Bennett, T., Jackson, A. V., Kuppermann, M., & McLemore, M. R. (2022). Clinicians' Perspectives on Racism and Black Women's Maternal Health. Women's Health Reports (New Rochelle, N.Y.), 3(1), 476–482. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2021.0148.

Chambers, B. D., Taylor, B., Nelson, T., Harrison, J., Bell, A., O'Leary, A., Arega, H. A., Hashemi, S., McKenzie-Sampson, S., Scott, K. A., Raine-Bennett, T., Jackson, A. V., Kuppermann, M., & McLemore, M. R. (2022). Clinicians' Perspectives on Racism and Black Women's Maternal Health. Women's Health Reports (New Rochelle, N.Y.), 3(1), 476–482. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2021.0148.

MacDorman, M.F., Thoma, M., Declerq, E., Howell, E.A. (2021). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Maternal Mortality in the United States Using Enhanced Vital Records, 2016‒2017. American Journal of Public Health 111, 1673_1681, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306375.

Beck C. T. (2015). Middle Range Theory of Traumatic Childbirth: The Ever-Widening Ripple Effect. Global qualitative nursing research, 2, 2333393615575313. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615575313.

Daniels, E., Arden-Close, E., & Mayers, A. (2020). Be quiet and man up: a qualitative questionnaire study into fathers who witnessed their Partner's birth trauma. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 20(1), 236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02902-2.

National Institute of Mental Health. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved August 10, 2023 from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd.

Ayers, S., Bond, R., Bertullies, S., & Wijma, K. (2016). The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychological medicine, 46(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002706.

McKenzie-McHarg, K., Ayers, S., Ford, E., Horsch, A., Jomeen, J., Sawyer, A., Stramrood, C., Thomson, G., & Slade, P. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: An update of current issues and recommendations for future research. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 33(3), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2015.1031646.

Dekel, S., Stuebe, C., & Dishy, G. (2017). Childbirth Induced Posttraumatic Stress Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Risk Factors. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 560. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560.