Infant Feeding and Parental Mental Health Fact Sheet

We are committed to curating the latest information in perinatal mental health to help educate healthcare providers, birth workers, and policymakers. This fact sheet is the screen reader version for those who prefer to consume their information in this format. We also have a PDF version available with the same information.

Download the Infant Feeding and Parental Mental Health Fact Sheet.

Key Facts: Maternal Mental Health (MMH) Conditions

1 in 5 Mothers Are Impacted by Mental Health Conditions

Maternal mental health (MMH) conditions are the MOST COMMON complication of pregnancy and birth, affecting 800,000 families each year in the U.S. [1,2]

Mental Health Conditions Are the Leading Cause of Maternal Deaths

Suicide and overdose are the LEADING CAUSE of death for women in the first year following pregnancy. [3]

Most Women Are Untreated, Increasing Risk of Negative Impacts

75% of women impacted by maternal mental health conditions REMAIN UNTREATED, increasing the risk of long-term negative impacts on mothers, babies, and families. [4]

$14 Billion: The Cost of Untreated Maternal Mental Health Conditions

The cost of not treating MMH conditions is $32,000 per mother-infant pair, or $14 BILLION each year in the U.S. [5]

Certain Individuals are at Increased Risk for Experiencing MMH Conditions

High-risk groups include people of color, those impacted by poverty, military service members, and military spouses. [6,7]

It's Not Just Postpartum Depression: There are a Range of MMH Conditions

MMH conditions can occur during pregnancy and up to one year following pregnancy and include depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar illness, psychosis, and substance use disorders. [8]

Learn More about Maternal Mental Health Conditions

Learn more about maternal mental health conditions with our Maternal Mental Health Fact Sheet.

Key Facts: Infant Feeding

Human milk is widely considered to be the optimal food for infants.

Human milk provides unique nutrients and antibodies that cannot be replicated; it can help protect against some childhood illnesses, and it is associated with decreased obesity and asthma in older children. [9,10]

Human milk is recommended for the first 6 months of infant feeding.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive human milk for the first 6 months of the infant’s life, with continued human milk provided alongside nutritious complementary foods for 2 years. [9]

There are positive physical benefits for lactating people.

People who lactate can also experience positive physical benefits, with decreased risk of ovarian and uterine cancers. [11]

Fewer than 25% of babies in the U.S. receive exclusive human milk at 6 months of age.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that while 83% of families initiate breast/chest feeding, less than 25% of babies in the U.S. receive exclusive human milk at 6 months of age. [11]

Terminology

Not all people who feed their infant from their body identify as women.

Providers should speak with patients about what terms feel most comfortable for them. Gender-neutral language is used throughout this Fact Sheet.

Inclusive and Gender Neutral Language Suggested by the National Institutes of Health [12]

Gender neutral alternatives to the term “breastfeeding”:

Chestfeeding

Bodyfeeding

Infant feeding

Human milk feeding

Gender neutral alternatives to the term “breast milk”:

Chest milk

Human milk

Gender neutral alternatives to the terms “mother” and “mom”:

Parent

Postpartum person

Birthing people

People capable of pregnancy

Hormones and Mood

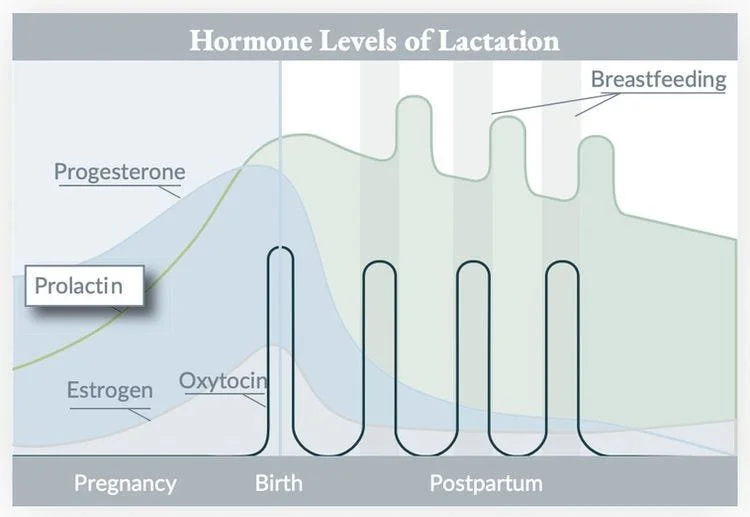

Complex hormonal changes associated with pregnancy and lactation can impact a parent's mood.

The significant drop in progesterone immediately following childbirth can have a negative impact on mood. Early breastfeeding / chestfeeding and skin-to-skin contact between parent and baby can help mitigate this phenomenon. In addition, increases in oxytocin, which stimulate milk release, often have a positive impact on mood during lactation—enhancing feelings of affection and bonding with the baby. [13]

Source: 2014 Article by Pamela K. Murphy, PhD, MS, APRN-BC, CNM, IBCLC, Director of Education, Research & Professional Development, Ameda, Inc. Graphic adapted from Love SM, Lindsey K. Dr. Susan Love’s Breast Book. 1st ed. MA: Addison-Wesley; 1990.

Some people experience unpleasant emotions related to lactation and breastfeeding / chestfeeding.

Dysphoric milk ejection reflex (d-MER) is a relatively common disorder wherein a lactating person can experience intense negative emotions (including sadness, loneliness, irritability, and rage) during milk letdown, either while pumping or breastfeeding / chestfeeding. Symptoms are usually transient, lasting 30 seconds to 2 minutes, and are thought to be associated with a drop in dopamine when milk is released. It can be helpful to acknowledge these distressing emotions and remind parents that they are physical, not psychological, changes. Learn More. [14]

Breast/chestfeeding can be protective of mood shifts when feeding is going well for families; conversely the stress of feeding difficulties can exacerbate mood disturbances.

Racial and Cultural Challenges

Culture, race, ethnicity, and infant feeding.

Infant feeding is a very personal decision that is infused with racial, cultural, and ethnic beliefs and values. Culturally respectful medical care that prioritizes the parents' realities and preferences as well as the infants' needs are essential. Increasing support by providers and increasing the number of culturally and racially diverse providers can help mitigate these challenges. [19,20]

Providers should train in culturally respectful care to ensure that they can support patients’ individual needs.

People across race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status can have very different experiences with infant feeding. It is important to honor and support each patient in a way that acknowledges their unique situation. [19]

Intersection of Infant Feeding and Parental Mental Health

The relationship between infant feeding and a new parent’s emotions can be complicated.

While many new parents experience joy, fulfillment, and feelings of being connected with their infant when breastfeeding / chestfeeding, other parents may struggle emotionally or physically with providing human milk, which can elicit negative feelings. [10]

New parents experiencing mental health conditions may feel conflicted about infant feeding.

When breastfeeding / chestfeeding is going well, it can be protective against negative moods. However, parents who experience a discordance between feeding expectations and actual experience are more likely to experience anxiety or depression. Some parents may wish to provide human milk, but are not able, or find it uncomfortable or unfulfilling, potentially leading to feelings of failure or inadequacy. Some parents may not want to provide human milk but feel enormous pressure to do so, possibly increasing their stress or anxiety. Some parents may wean earlier than anticipated, which can lead to emotions ranging from relief to grief. Still others may choose to provide human milk exclusively, feeding and pumping for many months. [10,15]

Every baby is different, and every infant feeding experience will be different.

Infant feeding can be stressful, especially if the baby is fussy or a fussy feeder; has reflux, colic, or allergies; is sleep-adverse; or is slow to gain weight or is diagnosed as “failure to thrive.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it is usually safe for individuals who are pregnant or lactating to initiate or continue taking prescription medications, including those that manage mental health conditions. [17] Learn More >

Lack of sleep or interrupted sleep can exacerbate MMH conditions.

Severe sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality are widely considered to be risk factors for MMH conditions. Creating a sleep plan to ensure that new parents get 4-5 hours of uninterrupted sleep, at least a few nights a week, can be protective. [10]

Providers and lactation consultants should take a trauma-informed approach when assisting parents who breastfeed / chestfeed as previous trauma can be an emotional trigger.

Providers should explicitly ask for permission before directly assisting parents with breastfeeding / chestfeeding, thoroughly explain actions before touching the parent or infant, and provide a safe physical space for feeding. Providers should also be prepared to discuss the dual role of breasts (as providing both sexual pleasure and nutrition) and conflicting emotions parents may experience about lactation, breastfeeding / chestfeeding, or pumping. [16]

It is usually safe to take prescribed medication, including those that manage mental health conditions.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it is usually safe for individuals who are pregnant or lactating to initiate or continue taking prescription medications, including those that manage mental health conditions. Physicians and other providers should be informed about medications their patients are taking and be prepared to discuss risks and benefits. [17] Learn more.

The infant formula shortage in the U.S. continues to cause stress for parents.

The U.S. has been experiencing an infant formula shortage since the spring of 2022, leaving many new parents feeling stressed and anxious as to how they will feed their infants. It is important to note that the vast majority of parents (over 75%) provide formula to their infant at some point, meaning that almost all families are impacted by the infant formula shortage. Providers can acknowledge the stress associated with the lack of control surrounding feeding an infant, and point patients to further resources. [18] Learn more.

Learn More about Infant Feeding

Don’t want to miss another fact sheet? Sign up for our newsletters!

Editorial Team

This fact sheet was prepared by Jennie Scheerer, MMHLA Policy Intern and 2024 MPP/MPH Candidate at the University of Michigan, with input from Susan Howard, MSN, RN, IBCLC. This fact sheet was funded by grants from the California Health Care Foundation and the W.K.Kellogg Foundation.

Citations

Fawcett, et al., 2019. The Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: A Multivariate Bayesian Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 80(4), 18r12527. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18r12527.

Gavin, et al., 2005. Perinatal depression: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106(5 Pt 1), 1071–1083. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db.

Trost, et al., 2022. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/data-mmrc.html.

Byatt, et al., 2015. Enhancing Participation in Depression Care in Outpatient Perinatal Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 126(5), 1048–1058. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001067.

Luca, et al., 2020. Financial Toll of Untreated Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders Among 2017 Births in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 110(6):888-896. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2020.305619.

United States Government Accountability Office, 2022. Defense Health Care: Prevalence of and Efforts to Screen and Treat Mental Health Conditions in Prenatal and Postpartum TRICARE Beneficiaries. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105136.pdf.

Center for American Progress, 2019. Eliminating Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Mortality. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/eliminating-racial-disparities-maternal-infant-mortality/.

Postpartum Support International, 2023. https://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/.

American Academy of Pediatrics, 2022. American Academy of Pediatrics Calls for More Support for Breastfeeding Mothers Within Updated Policy Recommendations. https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2022/american-academy-of-pediatrics-calls-for-more-support-for-breastfeeding-mothers-within-updated-policy-recommendations/.

McIntyre, et al., 2018. Breast Is Best. . . Except When It’s Not. Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association, 34(3), 575–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334418774011.

Bass, et al., 2020. Outcomes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2018 Breastfeeding Report Card: Public Policy Implications. The Journal of Pediatrics, 218,16-21.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.08.059.

National Institutes of Health, 2022. Inclusive and Gender-Neutral Language. https://www.nih.gov/nih-style-guide/inclusive-gender-neutral-language.

World Health Organization, 2009. The Physiological Basis of Breastfeeding. In Infant and Young Child Feeding: Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK148970/.

Heise, et al., 2011. Dysphoric milk ejection reflex: A case report. International Breastfeeding Journal, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4358-6-6.

Yuen, et al., 2022. The Effects of Breastfeeding on Maternal Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Journal of Women’s Health, 31(6), 787–807. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0504.

Kendall-Tackett, et al., 2013. Depression, Sleep Quality, and Maternal Well-Being in Postpartum Women with a History of Sexual Assault: A Comparison of Breastfeeding, Mixed-Feeding, and Formula-Feeding Mothers. Breastfeeding Medicine, 8(1), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0024.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023. Prescription Medication Use. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/vaccinations-medications-drugs/prescription-medication-use.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022. Information for Families During the Infant Formula Shortage. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/infantandtoddlernutrition/formula-feeding/infant-formula-shortage.html

Noble, et al., 2009. Cultural Competence of Healthcare Professionals Caring for Breastfeeding Mothers in Urban Areas. Breastfeeding Medicine, 4(4), 221–224. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2009.0020.

PBS News Hour, 2019. Racial Disparities Persist for Breastfeeding Moms: Here’s Why. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/racial-disparities-persist-for-breastfeeding-moms-heres-why.